Swarovski ATX 65mm vs 85mm lens comparison

A spotting scope can be one of the most valuable pieces of equipment in your pack. Whoever coined the saying ‘let your eyes do the walking’ was a wise person. A spotting scope can and will save you countless miles of hiking to evaluate animals, see what that flash of movement was under a tree across the draw, or count rings on a ram’s horns to determine their age. The number of situations where a spotting scope is beneficial are too many to count, and if you hunt anywhere that requires spotting animals from a distance, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

Today there are so many spotting scope options available. There are large and small objectives, angled and straight models, modular scopes where you can swap lenses, HD and non-HD…so many choices. This article is dedicated to a comparison of the Swarovski ATX lineup, specifically the 65 mm and 85 mm objective lenses, but much of the information can be applied to spotting scopes in general.

Swarovski has long been known as one of the top dogs in the spotting scope arena. The quality and clarity of their optics is nearly unrivaled. One of my favorite pieces of equipment from their lineup is the ATX/STX spotting scope. This is Swarovski’s modular spotting scope lineup, which allows you to swap out objective lenses with the same eyepiece. For most people, it’s unrealistic to own each size of objective lens they offer, but it certainly does give you a lot of options if you so desire!

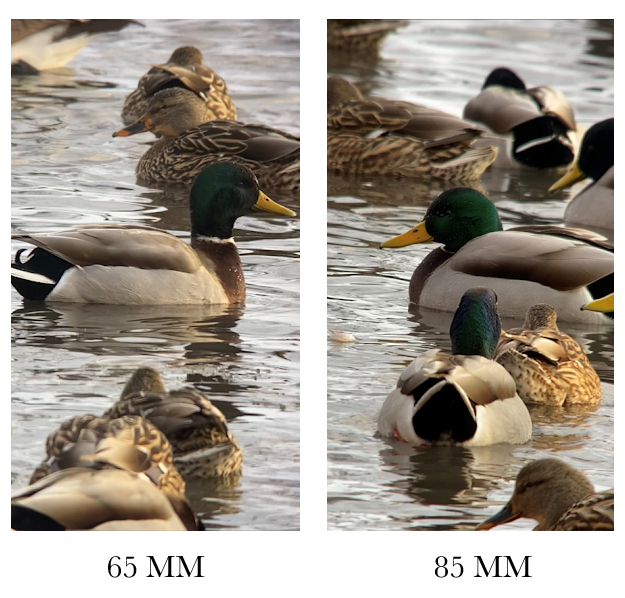

In this comparison, the quality of the images is nearly the same. When there is plenty of ambient light and you don't have to zoom in very much, the difference between the lenses is reduced to basically nothing thanks to the superb quality of Swarovski optics.

When I first invested in a Swarovski spotting scope, I decided to go with the ATX model eyepiece (ATX is the angled eyepiece; STX is the straight eyepiece), and I decided to pair it with the 65 mm objective lens. I chose this size of lens mainly for two reasons: price and packability. For reference, the ATX 65 is listed as weighing 55.9 oz, and the ATX 85 is listed at 67.4 oz. Both those weights are the angled eyepiece and the respective objective lens. Swarovski optics are not cheap, but I strongly believe the saying ‘you get what you pay for’ truly does apply to their products.

Terminology

Before diving in any further, here’s a couple optics-related terms to be familiar with:

- Eyepiece – what you look through with your eye.

- Objective lens – the opposite end of the scope from the eyepiece; the objective lens collects all available light and focuses that light.

- Magnification – the factor by which an image is enlarged, compared to viewing it with the naked eye.

- Exit pupil - the circle of light that you see when looking into an optical system. In an ideal setup, the entrance pupil of the viewer (your eye) must be perfectly aligned with the exit pupil of the instrument you’re looking through AND the exit pupil of the instrument and the entrance pupil of your eye would be the same size.

- Eye relief - the measurement of how far away your eye should be from the lens when looking through the optics.

In the picture on the right from the 85 mm lens, the green seems to really pop more and is more vibrant to my eyes. The details in that image also seem just a hair crisper.

After having gone on a few Dall sheep hunts with my 65 mm scope and having had the opportunity to count their annuli rings, I realized that a brighter image could very well be a game-changer since the larger lens would allow more light to pass through the scope, brightening the image. I decided to upgrade from the 65 mm lens to the 85 mm lens. I chose the 85 mm lens for price and packability (and weight). Some sheep hunters would call me crazy for packing an 85 mm lens, but personally I would rather be slightly heavier in my optics and scrimp to save weight in other gear categories in my pack.

The Differences:

With both the 65 mm and 85 mm lenses, the magnification range of the ATX scope is 25-60, so using either lens won’t give or take away magnification power. The key is how clear and bright the image will be when you’re zoomed in at higher powers and light is fading. This is essentially determined by the exit pupil value. You can calculate exit pupil by dividing the objective lens diameter (in millimeters) by the magnification factor. So, for an optic with variable magnification, there will be a range of exit pupil diameter values. You may realize without even doing any quick math that a scope set on its lowest magnification power will provide your eyes with the largest beam of light. As you increase the magnification, that beam of light gets smaller.

Low Light:

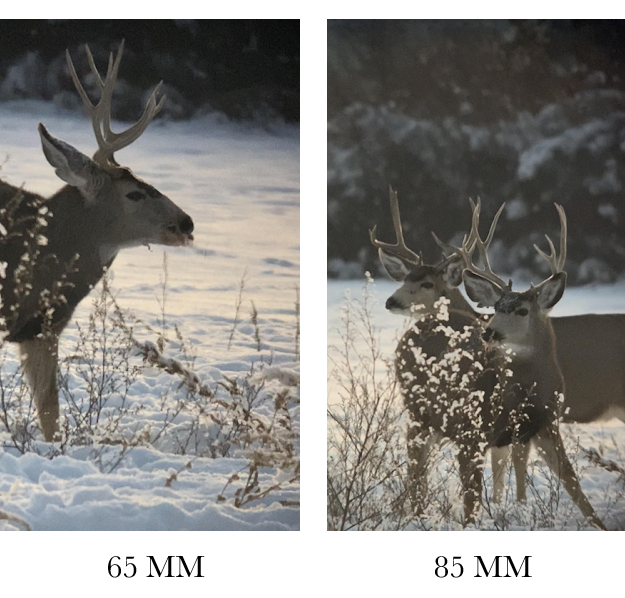

Both pictures were taken after the sun had sunk below the horizon. The left picture was taken first, so there was more ambient light still available. In the 2-3 minutes it took to take down my scope, swap lenses, get it on the tripod again and hook up phone to take another picture, there’d been a noticeable reduction of ambient light (to my naked eye). I think the images look very similar in brightness and quality because the larger objective lens compensated for having less light available.

Our pupils will dilate in low-light situations (think first or last light of the day). This allows more light into our eyes, making it easier to see, but the catch is there’s less light at those times of day to enter our eyes. This is why we like our optics to ‘collect’ or pass through as much light to our eyes (and dilated pupils) as possible. When it’s bright outside, our pupils constrict, allowing less light in.

So now you may be thinking that the larger the beam of light, the brighter an object will appear, right? Well, that depends. The pupil in the human eye is only capable of expanding so far, and thus can only take advantage of so much light. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, pupils generally range in size from 2 mm (constricted) to about 8 mm (fully dilated, or close to).

So, depending on the magnification power and objective lens size of your scope, you could have large exit pupil values, but essentially all that extra light is wasted since your pupils can only dilate so far and allow in so much light. Having that extra exit pupil margin can’t hurt the image your eye perceives, but just realize that as that number goes up your eyes are able to take less and less advantage of the light they’re being provided. Therefore, a scope with a higher magnification power and bigger objective lens will allow most people to zoom in and still see a clearer image than they would see when looking through a scope with a smaller objective lens and using the same magnification power. The scope with the bigger objective lens allows that exit pupil factor to stay within the ‘sweet spot’ range for most people’s eyes on higher power for a wider range of magnifications than the scope with the smaller objective lens can.

Another benefit of exit pupil is it allows us to get on target quicker when looking through a scope and our body isn’t perfectly aligned with the optical axis (think throwing your pack down, laying your rifle on it, and getting on target behind the gun to try and get a shot in the 5-6 seconds you’ve got before the buck is out of sight).

This is why exit pupil is a good number to keep in mind and know how to calculate, but since everyone’s eyes are different, the brightness of an image when looking through a certain scope will depend on that person’s eyes and not just the potential of the optical system for maximum exit pupil. Men in their 40s or 50s have the aging process to thank because at that age our pupils max dilated size shrinks from around 8 mm to the 5-6 mm range (isn’t getting old great?!).

In real world scenarios, there is only so much we can do to control all the variables that determine the effectiveness of an optical system, and that is why it’s SO IMPORTANT to test the optics you are thinking of buying to see what works best for YOUR eyes.

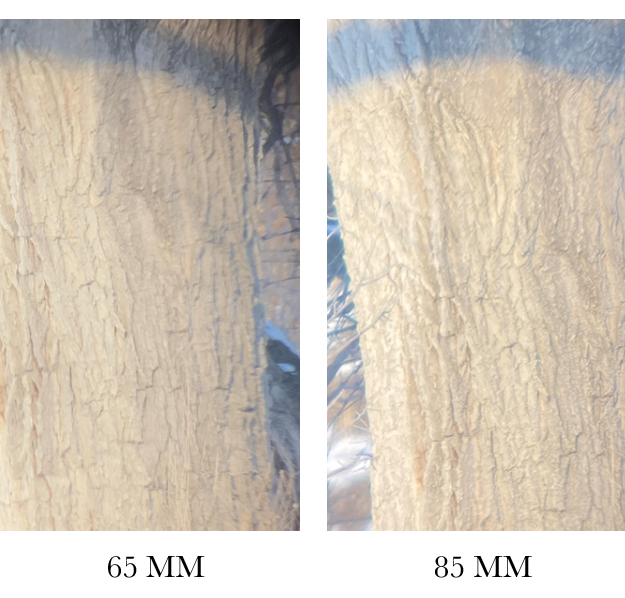

This is a very interesting side by side comparison. This tree is about 350 yards away. Both setups are on max zoom (60X). To my eyes there is more detail apparent on the tree in the image from the 85 mm lens. This made me think of trying to count rings on a ram to determine legality. Being able to distinguish very subtle details can make all the difference in that crucial moment.

My Take...

When it comes down to which objective lens I take, it usually depends on the application. If I am going to be needing to determine age on an animal, for example by counting age rings on a ram, I will lean towards the 85 mm objective lens since it will have a larger exit pupil and allow my eye to look at a brighter image. If I am going to sit on a mountainside and glass for cow elk across the canyon, I would take my spotter with the 65 mm objective lens because it’s lighter. Now if I’m being really honest, I have taken quite a liking to my 85 mm lens, and I’ve used it in situations where I really didn’t need it. I enjoy digiscoping, and simply seeing things in the clearest and brightest view possible. Now digiscoping is different from just looking through a scope. The fact that the image is being transmitted through multiple optical systems (that aren’t anywhere close to being calibrated for use together) prior to looking at the final image with your eyes will mean that you will lose a little (or a lot) or image quality. But it can still be a lot of fun, and it’s a great way to capture imagery of animals that we otherwise can’t get.

So, in conclusion, using the 65 mm vs 85 mm objective lens really does come down to personal preference and your application. Bigger isn’t always better when it comes to spotting scopes, but when it comes time to use that scope, bigger can’t hurt. I think personally I would recommend the 85 mm objective lens over the 65 mm (if you can only have one), but again it really is personal preference. If you have the means to, try them out for yourself and let your eyes decide for you.